The “We”ification of the youth is something I've wanted to talk about for over a year. I wrote an essay about the collective identity I see online well before I started Consumer Digest, or even knew what Substack was. This has been heavy on my mind and a critique of internet culture that is hard to get away from.

Everyday while scrolling I see a “we” statement that just feels utterly stupid to me. I hate to say it, but I have to be honest.

“Can WE stop wearing slick back buns, some of us have big foreheads”

“Where are WE buying swimsuits from for summer”

“Can WE normalize wearing xyz”

“Can WE bring back xyz”

In the words of my Mother “ You and who makes we?”

My question is, do YOU need permission to do everything? Do things need to be trending in order for you to do them? Like just do them. Do wear slick backs if you feel they make you look like you have a five head, wear that dress from 2008, do your makeup like it's 2016.

The obsession with collective aesthetics is actually harming you if the trends don't fit your style or facial features or most importantly preferences. Is asking for permission necessary?

I see this online nonstop and I’ll be self aware, it is the worst thing… probably not but does it annoy the life out of me… YES.

This is all about collectivity, so I’ll be serving this up Family-Style….

Let’s Digest!

The Appetizer

I’m calling this phenomenon “We-ification”, where individuals replace the singular pronoun “I” for the plural pronoun “We”. This is typically done when posing a question, instead of saying “I should start doing my eyebrows like it's 2016”, one might say “ We should do our eyebrows like it’s 2016”.

Now, why might one shift these personal decisions to collective decisions? I think this is an aspect of late stage social media, where individuals seek content that confirms their biases. They want the algorithm to regurgitate what they feed it and if it doesn’t the preference is to change the collective as opposed to the individual- which is themselves.While it's much easier to shape your brows than it is to shape others, most people desire the acceptance of the collective. They unknowingly avoid making individual decisions and look to their algorithm for guidance and social safety. The fear of being ostracized for not doing what the “we” does creates a dichotomy of self doubt.

This is mostly something we see with Gen Z and Gen Alpha, who—based on both vibes and anecdotal evidence—are never really alone. These are the social media kids, raised with constant access to each other, nonstop notifications, and yes, plenty of surveillance.

I have a 15-year old sister, and it dawned on me last week that she is always on FaceTime. Like, always. It’s almost like she can’t do anything unless there’s a friend on the other end of the screen. Getting ready? On FaceTime. On the way to school? Still on. In line for the bathroom? Yep. Feeding the dog? Of course. It’s this ongoing stream of “togetherness” where even the most mundane moments become shared experiences. What used to be solo tasks are now group activities. My initial reaction was frustration, but the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. This is probably why streaming is so big.

Streaming lets people feel like they’re hanging out, even when they’re not in the same place. You’re not just watching someone cook or game—you’re there with them. The experience feels live, present, communal. And for a generation that’s used to being plugged in 24/7, it fills the silence. It makes the digital space feel warm, casual, and alive.

Even when it isn't real.

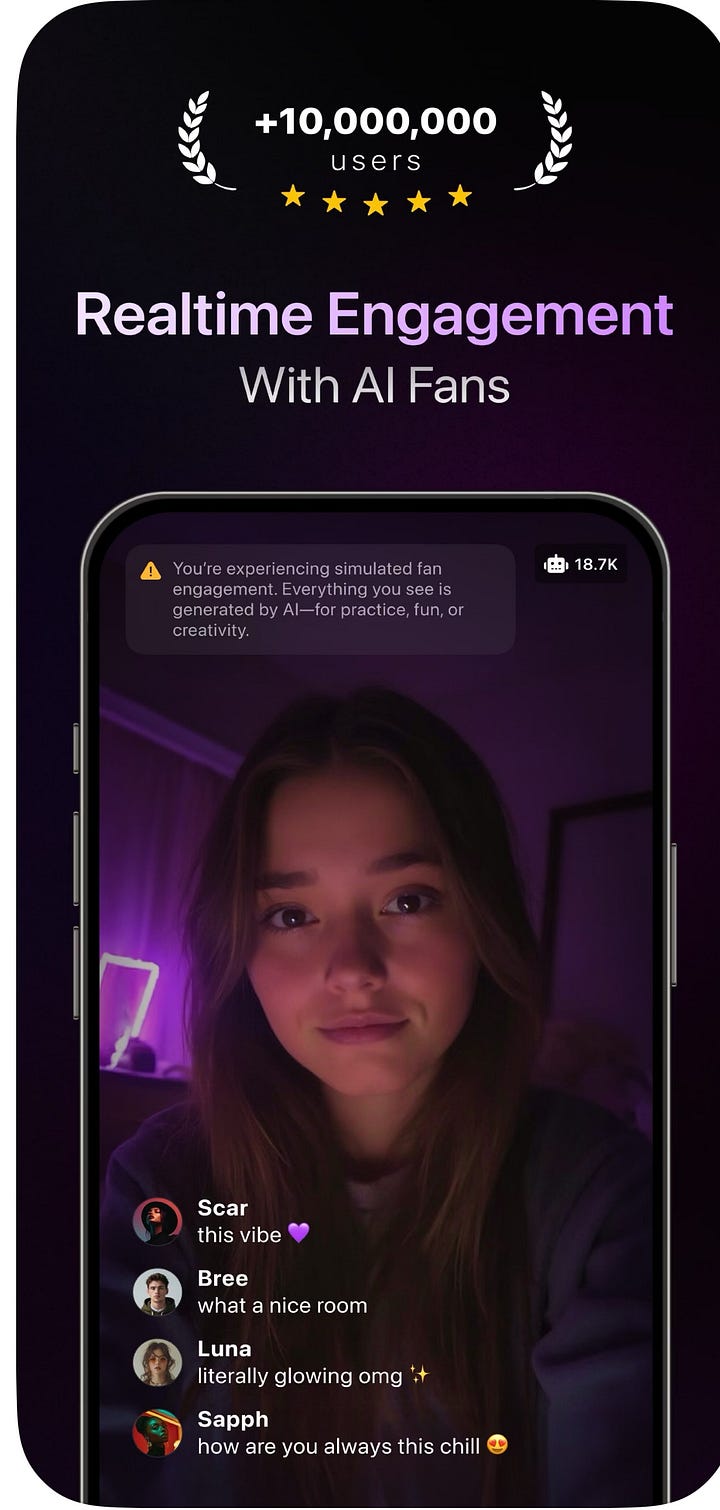

Having a little sister gives me an unfiltered look into what younger Gen-Z’s are really up to online. One of the most memorable things she’s introduced me to is an app called Famefy. It’s an AI-powered livestream simulator—basically, a fake stream with a fake audience. The app generates artificial comments, likes, viewers, and engagement so that users never feel like they’re broadcasting to an empty room. It gives you the illusion of being seen, even when no one’s watching.It's almost as though it meets an emotional need for feedback, interaction and the illusion of being part of something bigger.Not everybody can build an audience but with apps like Famefy anybody can have “imaginary fans”.

There’s something else happening too. All this constant FaceTime, streaming, dual-screen living—it starts to blur the lines between being someone who expresses themselves and being someone who’s constantly observed. Gen Z and Gen Alpha are growing up with the idea that you are content. You’re not just living your life, you’re performing it, sometimes without even realizing it.

At the same time, they’re less focused on the individual and more interested in the collective. Where Millennials were all about self-branding and being “unique,” younger generations seem more interested in being with others. There’s comfort in the group chat, the shared playlist, the random stream you leave on while doing homework. Being alone doesn’t feel alone if someone else is on the screen.

So yeah, the always-on FaceTime thing still drives me crazy, but I get it now. The group facetimes and stream chats is the new inner monologue. The “we” is stronger than the “I.” And honestly, in a world that feels overwhelming and uncertain,especially post Covid, it makes sense that young people want to move through it together.It’s not about the call—it’s about the connection.

The Main Course: The Psychology of Collective Identity

As readers of Consumer Digest know, I take the position that the internet is a real place—despite its frequent dismissal as some detached, alternate universe. In truth, for many people (especially younger generations), the internet is reality. What we see online doesn’t just reflect the world—it often defines it.

Sometimes, this is a psychological defense mechanism. Offline, we don’t always get to choose who surrounds us: our families, schools, cities. But online? The algorithm lets us build entire environments based on personal taste. You choose the creators you follow, the aesthetics you aspire to, the political takes you amplify, even the ads you tolerate. That’s a form of power, curation and control.

It’s no surprise, then, that people cancel influencers for being politically apathetic or tone-deaf, or that brands lose massive followings when their founders make insensitive comments (take a look at the viral video that has Set Active and it’s founder under criticism this week)

This isn’t just moral outrage—it’s psychological self-preservation. People protect their curated realities because it’s one of the few things they feel agency over.

What emerges from this is a kind of idealized digital world, where physical limitation- location, socioeconomic background, identity constraints start to dissolve. Social media democratizes access to community. You might be the “black sheep” of your hometown, but online you can find other black sheep, form a digital flock, and co-create an algorithmic ecosystem that reflects your worldview.

But, of course, this also leads to echo chambers.

An echo chamber is typically defined as a closed system where people are only exposed to opinions or beliefs that mirror their own, reinforcing their views and filtering out dissent. The term has been weaponized in political discourse to dismiss progressive ideas, but that’s not where I’m going with this. I want to focus on the psychological appeal of echo chambers, especially in the context of Gen Z and Gen Alpha’s digital behavior.

Studies in social identity theory and cognitive psychology have shown that humans are wired to seek belonging and affirmation. According to Henri Tajfel’s Social Identity Theory, part of our self-esteem is derived from group membership.When the group is perceived positively, so is the self. This is why even something as superficial as sharing a favorite influencer or wearing the same sweatset can become a powerful signal of “we-ness.”

Which brings me to the main point.

I’m calling this phenomenon We-ification: the tendency for individuals to replace “I” with “we” when posing a question, forming an opinion, or making a choice. It might sound small, but it signals something big. For example: instead of “I’m going to go back to my 2016 brows” someone might say “We need to start doing our brows like it's 2016 again.” Or “We need to stop romanticizing being busy.” It’s subtle collectivism, often not for organizing or activism, but for aesthetics, consumption, and self-worth.

It reflects a psychological shift. The overuse of “we” online blurs the boundaries between self and group—not always to take action, but to validate personal choices through imagined consensus. It's a coping mechanism, a social adhesive, and a branding strategy all at once.

As I wrote in Consumer Digest’s Is It Time to Drop Drops:

“Social media has transformed how we signal our tribes. Just as wearing a college sweatshirt or sports jersey once communicated belonging, today's digital natives use carefully curated consumer choices as conversation starters. It's the modern equivalent of a secret handshake – spot someone with the same Rhode phone case or Parke sweatset, and you've found a potential friend who shares your aesthetic values and cultural touchstones.”

This isn’t just about products. It’s about participation. It’s about being part of the “we.”

And the “We-ification” runs deeper than just visible consumption. It now influences even private, internal decisions—what to believe, what to support, how to spend your time, even what content feels worth watching. The self has become inseparable from the feed, and the feed is fed by the collective.

So while the internet may have started as a place to express individuality, it has evolved into what I call “Late Stage Social Media”, which is something else entirely: a place where the boundaries between me and we are constantly negotiated, blurred, and redefined—one post, one stream, one Facetime call at a time.

The Side Dish: The Economics of Collective Identity

If the psychology of We-ification explains how we’re drawn to collective identity, then the economics of it explains why we're willing to spend for it.

The neverending conversation of personal style on the internet is played out– people care more about signifying their belonging than their individuality. Fashion, beauty, and lifestyle choices don’t just communicate personal taste anymore… They function as social entry points. In the digital age, aesthetic alignment can serve as a proxy for shared values, status, and even friendship. Wearing a certain brand or following a certain trend grants access to belonging. Your personality is no longer just who you are—it’s what you signal. And in a world of algorithmic intimacy, signaling is everything.

This is where online echo chambers spill into real life. The ability to spot someone wearing a Rhode phone case or a Parke sweatset and instantly assume alignment—that’s not coincidence. That’s economic behavior driven by the need to belong.

What we’re seeing is a digital remix of the classic “keeping up with the Joneses” mentality. But instead of just your neighbors, you're now keeping up with thousands of micro-celebrities, influencers, and curated peers online. This maps directly onto James Duesenberry’s Relative Income Hypothesis, which argues that people’s consumption patterns are shaped not by their absolute income, but by how their lifestyle compares to others. In simpler terms: you don’t need more—you need more than them.

So when the collective aesthetic shifts, your purchasing behavior often shifts with it. Your spending becomes less about what you need and more about what you need to stay seen. Your consumption is no longer just personal—it’s participatory.

And while this might sound shallow, it taps into something deeper. According to Marx’s theory of commodity fetishism, humans start to assign social power and meaning to objects. We don’t just want the product; we want the feeling it promises. We want what it says about us. Objects become extensions of social capital.

Studies in consumer psychology back this up. Research shows that when people experience a threat to their self-worth, they are more likely to seek out high-status goods to compensate. In one study, individuals under self-threat demonstrated a stronger desire for status products but when offered a different way to restore their self-esteem (like affirming their values), that desire dropped. In short: consumption becomes a coping mechanism.

This brings us back to collectivity. In the age of We-ification, buying into a trend isn’t just about chasing aesthetics—it’s about restoring value to the self through the group. When the individual feels uncertain, the “we” becomes a balm. Participating in a shared aesthetic, buying the right items, aligning with the right creators—these are all economic acts that affirm your place in a collective.

And when belonging is scarce, we’ll pay a premium for it.

And Lastly, Dessert

The imagined consensus of social media’s “we” signals permission, allowing people to express their desires or queries without the fear of being ostracized. By bringing internal thoughts to the internet, you get a bounce board of responses, the likes, comments and engagement give permission to do something you never needed permission to do in the first place.

“We-ification” reflects a generational shift in how young people relate to identity, community, and even consumption. For Gen Z and Gen Alpha, the individual has become porous—shaped, validated, and often defined by the collective. Whether it’s FaceTime marathons or fake livestream audiences, the need to belong has been productized, aestheticized, and streamed in real time.

This isn’t just a linguistic quirk—it’s a new way of being. The “we” offers comfort, credibility, and community. It makes choices feel co-signed. It makes opinions feel less risky. It makes self-expression feel safer when it’s done as a group activity. But it also raises questions: What happens when individuality is filtered through consensus? When self-worth is tied to collective affirmation? When we start asking “Can we do this?” before ever asking, “Do I want to?”

Thanks for consuming!

Phia

“Each Day Gets Better”

Sources

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022103110000247

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1057740815000157

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0969698915300047

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0969698917303326

Wow this famefy app thing is fascinating!! The “we” thing really bothers me too, and it’s doubly interesting considering how much moral individualism has taken off in the digital age (the disappearance of close friends/neighborly relationships/“the village,” people saying that they “don’t owe anybody anything,” etc. it’s a striking contrast!

Love the coining, “We-ification.”